Partners in the Wild: How Agentic AI Amplifies Conservation

- Caroline Frisby

- Nov 11, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 12, 2025

By: Caroline Frisby and Angelina Kondrat

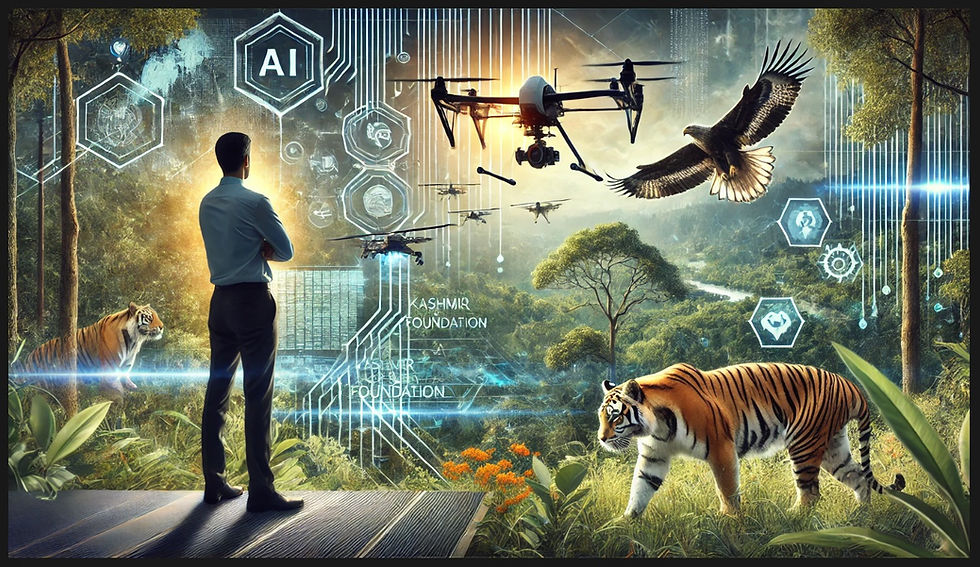

Kashmir World Foundation (KwF) has long been at the forefront of integrating artificial intelligence into wildlife conservation — from developing autonomous aerial systems like Eagle Ray to decoding animal communication through bioacoustic monitoring. Now, KwF is advancing this legacy with a new initiative: the Agentic AI Team.

This next evolution focuses on creating AI systems that not only analyze data but act independently and adaptively in real-world conservation environments. Through Agentic AI, KwF seeks to enhance situational awareness, improve field response, and empower nature-based intelligence systems that learn directly from the environments they help protect.

Led by geospatial analyst and early AI adopter Ian Shulkin, a team of five interns is pioneering a new approach to conservation through the development of Agentic AI. Unlike traditional AI models that rely on pre-coded decision trees, these systems can interpret complex instructions, interact with tools and APIs, and perform multi-step reasoning to determine which tasks to prioritize or defer.

The team aims to create AI agents capable not only of analyzing data, but also of making informed decisions and providing real-time support during field operations, transforming how conservation work is conducted.

“We want to look at things where the AI and agents can actually do some of that analysis, which previously required humans or strict coding,” said Shulkin. “For example, comparing a location image on one day with the next to identify changes or human activity, letting the system decide what’s important to investigate — all of this forms a multi-agent system.”

The goal isn’t to replace human expertise, but to free conservationists from hours of manual review and repetitive monitoring. “If we have agents working in real time during flights, we don’t need to train people for every task. With agents handling more work, we can onboard more team members with less training, which ultimately increases productivity,” said Shulkin.

Agentic AI technology in conservation is still in its early stages, and the surrounding hype can make it difficult to distinguish genuinely effective tools. To navigate this, the team conducts thorough research, compares different agentic frameworks and models, and evaluates both open-source and proprietary solutions under identical workflows. They experiment with prompts and data inputs to strike the right balance: too narrow, and the AI becomes overly specialized; too broad, and results can be inconsistent.

“It’s a whole battle between finding the right solution and the right balance to get the best answer,” Shulkin said, noting that AI outputs require careful tuning.

Despite these challenges, the team views this experimentation as crucial for uncovering the true potential of agentic AI in conservation, using trial and error to expand what the technology can achieve at KwF.

At KwF, Shulkin and his team are developing multi-agent systems to enable intuitive AI interaction across workflows and AI-assisted vehicle operations. Currently, Shulkin is testing a drone capable of receiving natural language commands, with the potential to execute complex flight plans. “Instead of having to go in and drop a bunch of points and change a bunch of drop-downs, I can just type out the general instructions,” he explained. This approach could allow less experienced team members to contribute more quickly, reducing the time and resources needed for training.

The system integrates multiple specialized agents: a gimbal control agent perceives the environment through the drone’s sensors and makes decisions, while an imagery analyst agent and a memory summarizing agent assist in processing and organizing data. A triage agent coordinates these specialists and efficiently delegates tasks. The team envisions secure, real-time communication with drones during missions. “If I need someone to give me more coverage over the area…having someone who can talk to it instead of programming would be a game changer,” Shulkin said.

By combining agentic AI with multi-agent architecture, KwF is building flexible, user-focused workflows that showcase AI’s potential. “If we have agents working in real time during flights, we won’t need to train new personnel for every task. By having agents handle more responsibilities, we can onboard additional team members with minimal training to support ongoing operations,” Shulkin explained.

Despite the system’s potential to increase productivity, several challenges remain. Certain types of data, such as geospatial datasets or specialized imagery from UV sensors, are not always available for conservation projects. To address these gaps Shulkin emphasizes the importance of collaboration and data sharing: “The more partnerships we make, the more data we’ll have available to experiment with our agents before we try to deploy them.”

When asked how Agentic AI fits into the broader conversation about AI sovereignty and collaboration in conservation, Shulkin emphasized the limitations of current technologies in addressing challenges rooted in terrain, culture, and communication. Conservation happens in places where people live, work, and rely on the land. “When surveying, you can have an effect on people, so you definitely need to understand the culture you’re working in,” he says, noting that conservation teams often operate in rugged terrain and where rangers may not speak the same language. Current AI models are rarely equipped for that level of nuance.

“Most models are trained for general patterns that the majority of people use worldwide,” Shulkin explained. “They won’t necessarily recognize the specific patterns of people who were in an area before a conservation project began, and won’t know that their presence isn’t abnormal.”

Until AI can interpret multiple languages and cultural contexts, sovereignty in conservation cannot simply be negotiated — it must be embedded into the systems themselves, as it is ethically important to ensure local knowledge is centered in decision-making processes. As artificial intelligence advances, Shulkin believes it cannot be ignored. “I don't think that means you necessarily need to code [to use AI],” he says. “I think knowing the pitfalls of it is really useful, though.” While artificial intelligence has significant potential for conservation, it can sometimes make mistakes. Shulkin advises understanding the AI’s purpose before using or investing in it, noting, “Even if it's not coding, learning how LLMs work and how you can improve them by providing context will help you spot the errors.” Despite these challenges, he remains optimistic about the future.

Over the next few weeks, Shulkin’s team will assist in part of a broader organizational move that involves relocating KwF headquarters from Virginia to Arkansas. They plan to develop cloud infrastructure to capture video and audio of wildlife and animals on the new property, with the goal of testing and interacting with agentic systems in real time, making improvements, and expanding the program with grant support. For the team, the move represents the beginning of a more hands-on chapter in their research. “I'm hoping that in the next few weeks we'll roll out some more interesting, physical things that people can see and maybe by the end of the semester start using,” he said.

“I think it's something everyone's looking forward to,” Shulkin says. “Being able to make everything less abstract and more hands-on will be really useful for us going forward.” Sharing important findings from the new headquarters can advance conservation efforts worldwide, such as providing a framework for more accurate data collection, monitoring, and countering criminal activities like poaching, wildlife trafficking, and illegal logging.

KwF recognizes that the survival of wildlife and the integrity of ecosystems are under increasing threat from illegal activities and habitat loss. When species disappear or populations decline, the delicate balance of ecosystems collapses, affecting predator-prey dynamics, plant regeneration, and overall biodiversity. Protecting these systems requires constant vigilance—yet there are simply not enough conservationists to monitor, analyze, and respond to every challenge in the wild.

This is where agentic AI becomes a powerful force multiplier for good. Implementing a multi-agent system will not only revolutionize current efforts, but also empower local participants to act as guardians of wildlife and long-term caretakers of ecosystems that affect them as well as the wildlife they seek to protect. By deploying multi-agent systems, KwF can observe, interpret, and act across complex ecosystems faster and more efficiently than traditional methods allow. Specialized AI agents track animal movements, monitor habitats, and analyze environmental changes, while triage systems coordinate responses in real time—expanding the reach and impact of conservation efforts far beyond what human teams alone could achieve.

KwF is stepping into a future where technology does not eclipse conservation, but enables it.

The vision is straightforward: systems adapt to the needs of the field, support the people protecting biodiversity, and strengthen the connection between communities and the environments they depend on. For Shulkin’s team, progress will unfold one experiment, one flight, at a time. Shulkin sees a clear destination ahead where artificial intelligence helps conservationists move faster, see further, and respond sooner. AI agents act as vigilant partners, giving wildlife a better chance to thrive, ensuring ecosystems remain resilient, and enabling humans to focus on stewardship rather than endless manual monitoring. In Shulkin’s vision, agentic AI does not replace human care—it multiplies it, creating a world where animals and their habitats finally receive the attention they deserve.

Comments